Sarah Knapton

The Telegraph

British scientists will face 'six minutes of terror' next week as the Schiaparelli space probe plunges to the surface of Mars after a seven month journey.

If successful, it will be the first time a European mission has landed on a planet. Although the ill-fated Beagle 2 probe made it to the surface of Mars in 2003, its solar panels failed to open after impact rendering it paralysed and unable to contact Earth.

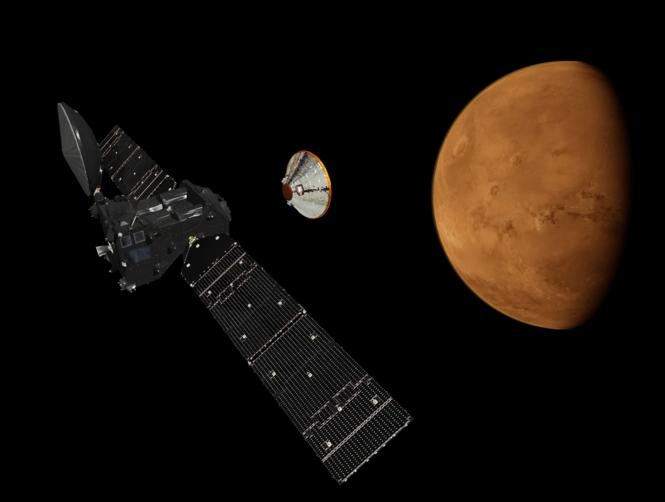

This time the scientists are taking no chances. The ExoMars mission has been split into two parts with Wednesday's landing acting as a dummy run ahead of the launch of a European rover in 2020 which will hunt for alien life.

The ExoMars spacecraft launched in March and will arrive at the Red Planet today after a 300 million mile journey before the lander 'Schiaparelli' begins its descent to the surface on Wednesday.

The little probe has a short battery life, so will only operate for a few days. The main point of the mission is simply to see if it can be brought down safely, with all its instruments intact.

But it will not all be plain sailing. The lander has to enter the Martian atmosphere at exactly the right angle and carry out a series of operations - timed to the second - if it is to get to the surface in one piece.

Dr Stephen Lewis, of the Open University, who is the co-principal investigator for the Amelia instrument, said: "This is really a test to see if we can land on Mars. We are learning how to do it and seeing if we have all our calculations right.

"This is absolutely crucial for Europe because we have fallen a bit behind. We have never successfully landed on a planet.

"It will be nerve-wracking six minutes of terror and by that stage there is nothing anyone can do if things go wrong, and there are 100 things that need to go right.

"These are incredibly complicated machines, and everything has to work, so all you can do is cross your fingers.

"There is also danger that a probe could bring bacteria from Earth. It would be dreadful if we sent a rover up looking for life and the readings were tainted by microbes we brought ourselves."

Dr Lewis knows first-hand the heartbreak of losing a spacecraft which has been decades in the planning. He was part of Nasa's Mars Climate Orbiter team which disintegrated after entering Mars' atmosphere at a lower than anticipated altitude in September 1999.

"I've worked on missions which have failed and it is just totally devastating," he said. "It sounds silly but it is like a family member has died. You watch it coming round the planet and then it is gone forever."

The disc-shaped module measures 7.8ft (2.4m) across with its heatshield and weighs 1,300lb (600kg). As it plunges to the ground, the on-board Amelia instrument will be take a host of measurements, including monitoring gravity, thermal tides, temperature and atmospheric pressure.

Once on the surface, separate instruments will sample the humidity and dust at the landing site - a flat region of Mars known as Meridani Planum, near the equator. Touchdown is close to Nasa's Opportunity rover and there is a chance the robot will capture a photograph of the probe coming in to land.

But the major science programme will not begin until 2020 when a hi-tech rover will be launched which will drill six and a half foot into the surface of Mars hunting for alien life. Nasa rovers can only currently drill two inches down.

Mars is thought to be the best chance of finding evidence of extra-terrestrial life because it once had running water and an atmosphere. The hope of discovering life was also raised in December 2014 when intriguing burps of methane were recorded by Nasa's curiosity rover.

On Earth, around 90 per cent of methane is produced by organisms, so the expectation is that some kind of life is also emitting the gas on Mars.

While Schiaparelli's goal is demonstrating how to land, the ExoMars orbiter is tasked with sniffing out rare gases like methane in the atmosphere.

In an essay in the new book Aliens Professor Monica Grady, of the Open University said methane could provide the crucial evidence for life on Mars.

"Methane is destroyed by ultraviolet radiation, so its presence implies an active source that continuously replenishes the atmosphere.

"The sources may be abiotic, such as the weathering of silicate rocks. Methane may also have a biological source. On Earth, termites and ruminants are major methane producers - the gas is generated internally by bacteria living in their digestive systems.

"Indeed, microrganisms in a variety of habitats are the main source of methane on Earth."

Microbial life has been found to live more than one mile beneath the surface of the Witwatersrand basin in South Africa so scientists are sure microbes could survive below the permafrost.

Scientists are also facing a tricky manoeuvre to re-orientate the ExoMars orbiter after it drops off the probe.

"They are now on a high-speed collision course with Mars, which is fine for the lander - it will stay on this path to make its controlled landing," said flight director Michel Denis at mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.

"However, to get the mothership into orbit, we must make a small but vital adjustment on 17 October to ensure it avoids the planet. And on 19 October it must fire its engine at a precise time for 139 minutes to brake into orbit.

"We get just a single chance."